Learning letter names and sounds can be a tricky process for English Language Learners. There are 54 letter forms in the English language–26 uppercase and 28 lowercase (including typeset “a” and “g”)–that students need to master in order to become successful readers and writers. Even trickier, many of the letters in the English language change their sounds depending on their positions in words.

city/crab

bridge/gate

yellow/many

According to Marie Clay, a psychologist and researcher from New Zealand, students learn letters at their own pace and in no particular sequence. The alphabet is simply a way of organizing letters, not an order by which letters can, or should, be learned. How quickly ELLs learn letters and letter sounds is influenced by prior knowledge and experience, age, schooling (if any), and other factors. In short, it’s personal.

Clay notes that learning the entire alphabet is overwhelming. Visual recognition of letter features builds up slowly, and discoveries do not occur in alphabetical order. As learners tune in to letter features, they’ll begin to expend less energy on what they already know, freeing up their brains to take on new information.

Clay notes that learning the entire alphabet is overwhelming. Visual recognition of letter features builds up slowly, and discoveries do not occur in alphabetical order. As learners tune in to letter features, they’ll begin to expend less energy on what they already know, freeing up their brains to take on new information.

One tool teachers can use to help students take on the alphabet task is an alphabet book. An alphabet book is a handmade, personalized record of letters that the student has mastered. This resource can be used to rehearse and extend students’ knowledge of letter names and link them to sounds in words.

Published "letter books" often contain an excessive number of images that are unknown to ELLs. Additionally, these texts generally represent only one dialect of spoken English. Consider how the various North American accents affect vowels sounds, in particular. Trying to decipher these texts may further complicate an already daunting challenge. Unlike these published texts, a handmade alphabet book contains only one straightforward example that students can immediately recall.

Getting started with an alphabet book is simple and can be made with supplies you may already have in your classroom. Follow the steps below to construct your own alphabet books and strengthen your students' letter knowledge with explicit, individualized instruction.

Alphabet books are not necessary for every student. Reserve alphabet books for students who are having difficulty identifying letters or distinguishing between letter sounds introduced in the classroom.

Administer a letter assessment of both upper and lowercase letters to determine what letters and/or letter sounds your students know. Letter assessments are readily available online and embedded in a variety of published assessment materials including, for example, Marie Clay's An Observational Survey of Early Literacy Achievement, Fountas and Pinnell's Benchmark Assessment System, the Phonological Awareness Literacy Screening for Kindergarten (PALS-K) and Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills (DIBELS).

ELLs with prior schooling already have some letter/sound knowledge in their home language. Note which letters and sounds are similar to English. For example, the letter "m" makes the /m/ sound in both English and Spanish. You might start by recording the letters of the sounds students know in the alphabet book.

Cardstock and plastic combs make the best alphabet books. Stapled, paper books tend to be bulky. Cardstock is heavier than paper and less likely to tear. Plastic combs (if you have a binding machine) make turning pages easy for little hands and allow the books to stay open without much effort. No binding machine? A ring of index cards will also do the trick!

Each page of the alphabet book is reserved for one letter pair–matching upper and lowercase letters–beginning with Aa and ending with Zz. Leave space for a small picture. For beginning readers, it's helpful to use landscape orientation to encourage left to right movement across the page.

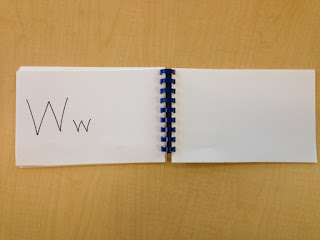

Use your assessment to record only the letters the students knows in the book, leaving unknown letter pages blank. For example, the student below can recognize the letter "Ww," but not the letter "Xx."

Start building a library of images using resources you already have. A small file box with alphabet dividers is great way to store pictures for easy access. Many published language and literacy resources contain appendices and resources that can be cut and copied. Some of our favorites are the Appendix of Guided Reading, by Fountas and Pinnell and the Word by Word Basic Picture Dictionary by Molinsky & Bliss. You can also supplement your picture supply with clip art from the internet, magazines, and photographs of classmates or objects from around the school and home.

Be sure to include pictures and photos with environmental print. These can be familiar places and businesses in the local community or name brands of toys and games. Often these words are more familiar to our students than those in published sources. Be culturally responsive in your selection of images. Consider the experiences of your students.

Use your assessment to record only the letters the students knows in the book, leaving unknown letter pages blank. For example, the student below can recognize the letter "Ww," but not the letter "Xx."

To start, open the book to a page labeled with a known letter. Lay 3-4 pictures beginning with that same letter sound in front of the students. Ask them to choose their favorite. Pictures should be simple and match the experiences of the child, e.g. “boy”, “boat”, “bug” for Bb. It's imperative that we are "working with the child's memory store, not with the teacher's favourites," says Clay.

Add additional letters to their reserved pages as you observe students recognizing them during lessons, in writing, or through assessment.

As noted above, some letter sounds transfer from one language to the next. For ELLs that have control of the letter sound, but not the name, you'll want to name the letter for them until they can do it independently. Students can glue in appropriate student-selected images for those letters as they learn the English words for them.

Students can read the alphabet book daily as a warm-up to the lesson, or as a “Familiar Read” to build letter-naming fluency.

I teach students to read each letter name and then the name of the picture ("R-r-rabbit”).

Some teachers might ask students to utter the sounds of the letters. Whichever way you choose, stick to it. Questioning your students about multiple features of the letters, such as their names, their sounds, which are curved, straight, etc. during the reading of the alphabet book can be overwhelming and may confuse young learners just beginning to distinguish letter forms.

The alphabet book is a tool that helps students link their letter knowledge in isolation to other reading, writing, and word work activities.

Provide opportunities for students to make a link between the letters and their sounds during Guided Reading or writing lessons. Use explicit prompting to connect the sounds to the student-selected pictures in their alphabet books. For example, say: "It says /g/ like 'goat' in your letter book," or, "It says /b/ like 'bike' in your letter book."

Provide opportunities for students to make a link between the letters and their sounds during Guided Reading or writing lessons. Use explicit prompting to connect the sounds to the student-selected pictures in their alphabet books. For example, say: "It says /g/ like 'goat' in your letter book," or, "It says /b/ like 'bike' in your letter book."

One of your instructional goals, for example, might be to teach students how to listen for and write the first sound they hear in words. During an Interactive Writing lesson, prompt students to link their known letters, recorded in the alphabet book, to the writing of new words. You may say, “The word ‘like’ goes here. ‘Like’ starts like ‘lion’ in your Alphabet Book.”

During a reading lesson, help students attend to letters in text by prompting them to self-correct. “Is it ‘rabbit’ or ‘bunny’? It starts like ‘run’ in your alphabet book, so it must be ‘rabbit’.”

A final note...

Avoid the temptation to clutter the alphabet book with additional vocabulary or word study notes. The purpose of the book is to offer students a way to distinguish or identify a letter from the other marks on a page. One simple image helps students make clear, direct links between letters and sounds.

Keep in mind that some of your students may not learn letter names and sounds at the same rate as other students in the class or in the order that you taught them. Reassure students that it takes time to build an alphabet book. Blank pages reassure students that learning is a personal process, and that it's OK to "skip over" a task that they're not yet ready to tackle. Your students will get a sense of accomplishment and progress as they watch the pages fill up with new learning.

An alphabet book can easily be integrated into your literacy routines. We have found this tool to be a simple and effective way to scaffold the learning of letters and sounds in English. Are you using alphabet books? We'd love to hear about it..share your experiences below!